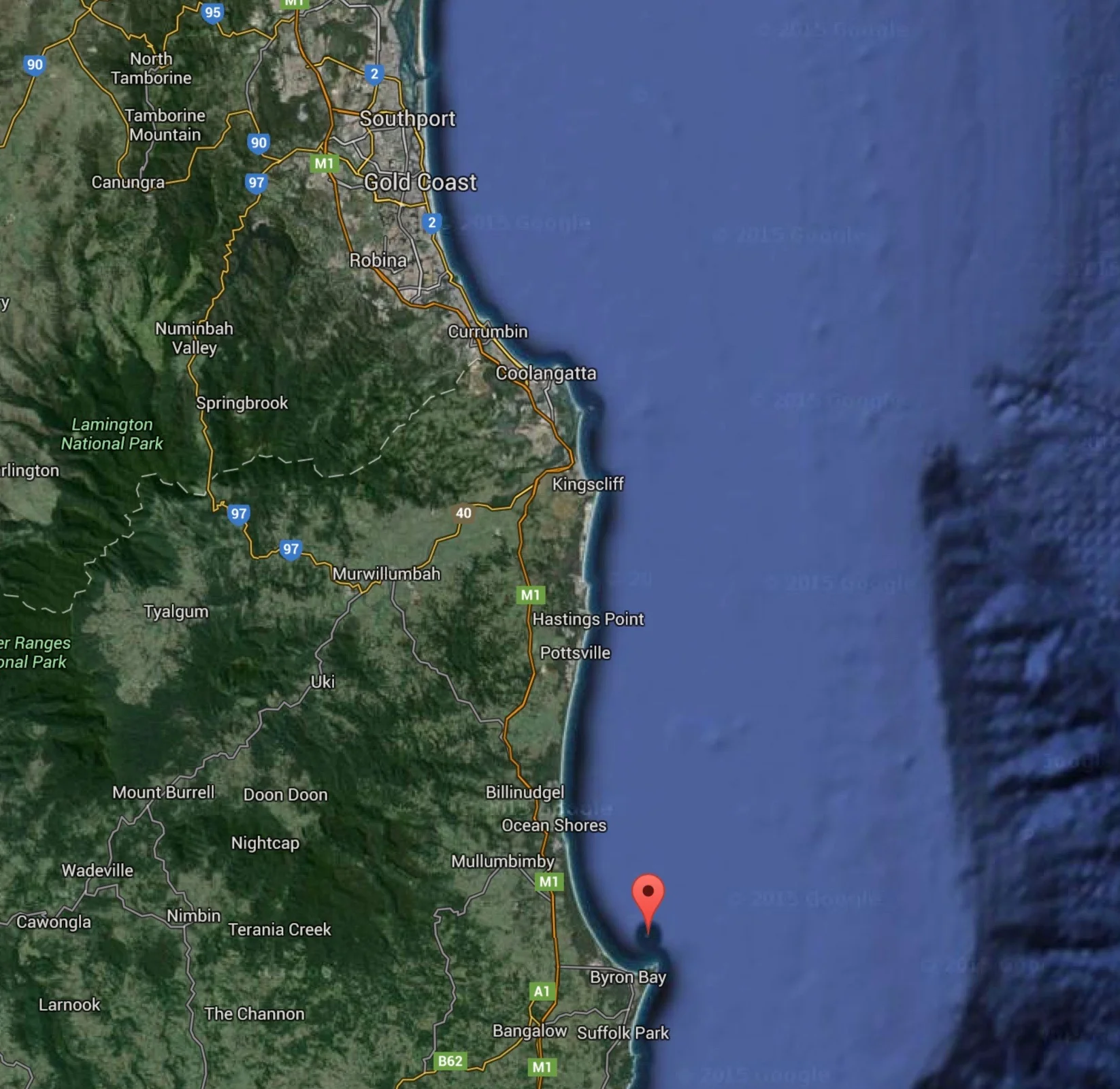

Yesterday saw Ocean Gem compete in Southport Yacht Club's Annual Julian Rocks Race. This race starts of Main Beach, near Southport on the Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia and heads 42nm south to Julian Rocks, a landmark off Byron Byron in New South Wales, which we leave to starboard, before returning the 42nm north to the finish line.

The race starts off Main Beach (Southport) in the North and heads 42nm south and around Julian Rocks off Byron Bay (red marker) then home to the finish off Main Beach.

In 2014 and 2015 when we competed in the winds were N-NE, resulting in a fast and enjoyable 6-7 hour downwind sail to Julian Rocks and then a long 12-13 hour uphill sail against both wind, swell and prevailing 1-1.5 knot southerly current.

Upwind sailing with our old dacron cruising sails (including a furling genoa) had always been our weakness. We could not point well upwind and performed even poorer in 15+ knots as soon as we had to start reefing our main and partially furl the genoa. In 2014 our elapsed time was 19.5 hours and in 2015 we completed the Julian Rocks race in 18 hours in 10-15 NE winds and no swell, versus the 20 knot northerlies and 2-3m seas the year prior. This year with new carbon racing sails, we were excited about our potential to perform much better than previous years.

This year the forecast was for SE 14 knots for our race start at 0700, easing progressively to ESE 8-10 knots later in the day. Research on Windyty.com, (which I rate really highly) forecasted that the change to ESE would have already happened 10nm offshore by the time the race started. Our east coast Australian current flows from north to south at 0.7-1.3 knots inshore and steadily increases as you head further offshore. The most I have experienced is a 3-3.5 knot current 30-35 nm offshore, which adds a hell of a lot to your boat speed if you are heading south with the current.

Yachts headed out through the seaway to the start line about 6:30am. Fourlove and Race Control in foreground

Our initial heading to the first waypoint would be 150 degrees, off the start line to Point Danger at Tweed heads, before altering course to 167 degrees the rest of the way to Julian Rocks, off Byron Bay. The gamble we decided to take off the start line was to head east on a heading of 090-100 degrees and head at least 10nm offshore until we found the ESE breeze (left hand shift), so we could tack onto the lifting breeze before the rest of the fleet and head directly to Byron Bay in stronger current. We had a good start, off the pin end of the line and headed east on a starboard tack. The fleet of 12 competitors followed us off the start line, but one by one over the next hour, most tacked back onto a course of 190-200 on a more direct course to the next waypoint and by heading back inshore toward the coast.

The fleet heads off the start line to windward of Ocean Gem. Leeway was our target to beat on left.

When you make a decision to go in the opposite direction to most of the fleet, it takes courage to stick with your convictions (or stupidity) in the face of mounting evidence that you have made the wrong call. As we headed due east for the first 90 minutes, sailing into the SE breeze as it veered progressively to ESE, our course heading dialled down from 090-100 to 060-070 as we started heading ENE and away from our southerly target (sailing 45 degrees off the true wind direction). We were only 10 minutes into this increasingly big 'knock', when we decided to tack onto port on a heading toward the next waypoint. Initially our heading was 160-170 degrees and it felt good, but within 10 minutes we had been knocked and our heading had changed to 190-200 degrees.

What we realised was that we had sailed into the edge of the new wind and back out of it again, without biting into it far enough. We discussed our options as a crew and decided we were committed to the strategy and tacked back onto starboard and sailed for the next 30 minutes on a heading of 100 degrees and watched it dial back down to 060-065 on a heading better suited for Fiji!

A picture of Ocean Gem heading offshore to the east, taken from a crew member on a competing yacht

By the time we were 2 hours into the race, we were 13nm offshore and the most eastern boat in the fleet by a long way. It was now time to tack onto port and start heading for Julian Rocks. It felt a little strange to be 2 hours into a race with no VMG (velocity made good) towards the next mark. Part of my gamble was also that being further offshore would put us into stronger tail current, than those tacking their way down the shoreline in shallower water.

Three yachts in the fleet of 12 were rated faster than Ocean Gem on our club PHS handicap;

- Leeway; a Sydney 38 who won the IRC Passage title at Airlie Beach Race Week in 2015.

- Cyclone; a Frers 50 that was originally commissioned by Max Ryan from Sydney in 1990 and rumour has it; was the first $1 million 50 footer in Australia. Cyclone went to the Admirals Cup in 1991 where Australia came dead last. Max hated the "slow moving depression" name tag, so he bailed out of it not to long after that, where it came to Queensland as part of some business swap and then was on-sold locally.

- Slyfox; a 42ft, light displacement, water ballasted yacht with twin rudders and retractable fin with a bulb. She was designed and built entirely by Mike Sabin over 4 years and launched in 1996 before setting of with his wife on a 7 year circumnavigation.

Slyfox; light, skinny and fast upwind

We finally tack onto port on a heading of 170, only 3 degrees above our waypoint (still 42nm away) at Julian Rocks. As we sailed south, the fleet were specs on the horizon with all of them well south and inshore of our current position. We focused on rotating hourly between 3 helmsman (myself, Rick and Karl) as we sailed south under full mainsail and number 2 genoa. Our focus was on steering to maintain a steady 7.5-7.8 knots boat speed, by steering to the genoa telltales rather than watching instruments. By the time a further 2 hours had passed, we had made good ground, heading directly for our mark, while those further inshore and ahead of us, had to tack repeatedly offshore to clear the coast as they zig zagged south.

Peter

The first heartening sign was seeing Leeway two miles inshore of us and headed toward us on a starboard tack. From the distance it was touch and go, trying to determine who was going to cross in front. As we sailed within half a nautical mile of Leeway, we looked like we were comfortably in front, but they tacked back onto port and headed back inshore, denying us the opportunity to cross in front of their path.

We sailed on and could see Sly Fox hard against the coastline and at least 2nm further south of us and Cyclone about 1nm south and headed east on a tack that would have us cross each other. Cyclone is much faster upwind and should have been comfortably ahead of us by now, so we watched with interest as she crossed about four boat lengths in front of us, four hours into the race, before tacking back onto the same southerly heading as us, on a port tack.

Rolling over the top of Cyclone after they lee-bow us. A rare feat.

At this point we realised our strategy had paid off and we had definitely gained an advantage wth only two yachts ahead of us. As we trailed Cyclone, we realised we need to tack away or sail lower and faster to overtake below her and get out of the disturbed air she was throwing at us. We were on a lifting tack, so taking away was not attractive. Watching Cyclone ahead of us, we could see they were pointing as high as possible, causing us to choke our sails and lose boat speed. We adjusted our heading, 10 degrees, eased our sails and Cyclone watch as we sailed past below them, overtaking them upwind, something we had not done before.

We sailed on, they tacked away and we started to get sail into a deepening knock as the wind swung right, affected by the land. We tacked back out to the east and saw Cyclone on an opposing tack about 1nm away on what appeared to be a collision course. We were on starboard with right of way and as we got closer I could see they could not successfully cross in front of us. I wanted to carry on on this tack and did not want them doing a lee-bow tack in front of us as it would force us to tack away to get clear air. I motioned their skipper to sail on and cross in front of us and started to dip my bow below their stern. Whether he did not see my gesture or he suddenly realised he would be at fault if there was a collision and reacted suddenly, I am not sure, be he threw his helm over and suddenly tacked in front of us into our path.

I had to react quickly and point the bow up to avoid a collision, but now my sails were stalling. There was silence on both boats and no one said a word as they beared away slightly, given us the ability to point of bow lower, fill our sails, gather speed and roll quietly over the top of them. Its rare that a 45 foot Beneteau gets to do that to a 50 foot racer like Cyclone.

A picture of our crew shot from another boat

Buoyed by our turn of speed, we sailed on towards Julian Rocks as we saw Leeway come back into view and tack onto our line about half a nautical mile astern. We did a couple more tacks into and back off the coast before settling on the lay-line to Julian Rocks. Inshore we had watched Slyfox continue to zigzag down the coast, closely inshore in what appeared to be different and lighter breeze. We simply sailed around her with amazement, as we realised we had come from about 2nm astern and were now well ahead and also at least 1nm to windward and on the lay-line to the half way point in the race, Julian Rocks off Byron Bay.

What happened next caught us by surprise, Sly Fox finally decided to head east and get away from the shoreline, sailed past our stern at least 1.5nm behind us and instead of tacking onto our lay-line, carried on for at least another 1-1.5nm. We then watched Cyclone cross our stern and also head at least 1nm above our lay-line, before tacking back onto the course to Julian Rocks. We were only about 5nm from the mark now and figured that unless we suffered a big knock (20-30 degrees), that we were perfectly positioned to lead the fleet round the mark, as we realised the two fastest yachts in the fleet had seriously overlaid it and cost themselves several minutes in lost time in the process.

Leading the fleet around Julian Rocks with Cyclone approaching in 2nd place in the right of the picture

We hit Julian Rocks, rounding at least 200 metres off the rocks as required by race rules and had our Code 0 ready to pop open. As we squared up on our heading to Point Danger on a course of about 330 degrees I realised I have worked out our down wind angles incorrectly and at 150 degrees TWD, we should have out the spinnaker up instead. We had not choice but to drop the Code 0, run bareheaded at half speed for about 3 minutes while the crew did a faultless change over.

With the spinnaker set, our speed jumped from 4 knots to 8 knots+ as we watched Cyclones big spinnaker looming up on the horizon about 1nm astern. We sailed on for the next 4 hours watching Cyclone creeping closer, but somehow they did just not have enough to get past us. Anytime the winds is 150-180 degrees we seem to be able to hold faster boats at bay, who really perform better when sailing their 120-140 degree angles.

Cyclone lurking behind us like a tiger for more than 4 hours, just waiting for the chance to pounce.

Meanwhile, Slyfox had no choice but to sail the downwind angles and after leaving Julian Rocks they were headed off to the NE on a course 30 degrees wider than our direct line to the next way point. It must be tough knowing you have to sail at least 30% faster than your competitor, to make up for the fact you are sailing 30% further, due to the wider downwind angles.

As we hit Point Danger, we had to bear away another 15-20 degrees and be sailing almost dead downwind for the final 2.5-3 hours to the finish line off the sand pumping jetty at Main Beach, Gold Coast, Queensland. We we still in front and had a real chance now of taking line honours. Leeway was at least 4nm astern, Slyfox was astern and well to the east sailing her angles and now Cyclone was forced to sail a higher course than us and were unable to sail our direct downwind angles.

We saw Cyclone put up a jib and drop their asymmetrical spinnaker as we figured they were due to through up their big symmetrical kite. Then a strange thing happened, they appeared to have problems on the foredeck and shortly afterwards they had taken down all head/downwind sails and now they we sailing under mainsail only. A short while later they retired from the race with halyard problems, a sad outcome for them after 10+ hours of racing. As much as its satisfying to beat a competitor in the water, its never great to see a crew forced to retire early from a race with gear problems.

Rick and Sean

We started to think that a line honours win was now a possibility and it seemed a far cry from the previous 2 years, when we had finished last across the line 2 years ago and 6th last year. Leeway was not going to catch us and all that left with a shot was was Slyfox, that we could just make out on the horizon, with their big chocolate brown asymmetrical spinnaker up, 3nm east of us as darkness fell. We had 70nm in the bag now and just 12nm to go, surely it was just a matter of finishing. Our ETA was looking like 7:30pm Saturday, which was remarkable given we had finished after 1am Sunday in the 2 previous years.

Then it turned to custard!

Karl was on the helm and I was trimming the spinnaker as darkness set in. The wind was shifting around a little and Karl was getting use to balancing the compass heading, steering to a 150-160 degree true wind direction and managing the slight sea state, which wanted to pick up the stern and shift it 30 degrees sideways every so often. We had a couple of near misses with pointing too high and the spinnaker luffing before starting to wrap around the forestay.

Sun setting over Tweed Heads

Fortunately a quick bear away fixed it as the big 1,000 square foot sail unwrapped and filled again. Forth time unlucky. This time it was different as the bow came up to far and the spinnaker deflated and started to wrap and wrap and warp around the forestay. As it wound round and round ten or more times, you hope it will simply unwind, but deep down you know, this could be one hell of a problem.

The genoa had been dropped onto the deck and tied down, after we hoisted the spinnaker and the halyard had been left attached to it. What that meant was the spinnaker had become snagged up high between the forestay and the halyard and that was enough to stop it unwrapping after wrapping initially. If the genoa halyard and been tied off back at the mast, it probably would have prevented the mess we now had.

Nothing we did would unravel it, the top third was still filling, but the bottom half was wound tightly around the forestay so hard that it had turned the genoa foil like a corkscrew and twisted the flat 60 foot line piece of high strength plastic through at least 360 degrees. If that cracked and broke as well under the load, this could really get expensive. The only solution was to send someone to the top of the mast, to unravel the mess from the top down, but on a moving boat, in the dark with a 1 metre swell, there was no way it would be safe to do that.

Our boat speed under mainsail only had dropped to barely 5 knots from the 8-9 we had been doing and now instead of being 30 minutes from the finish, it was closer to 50. When you are racing and something goes wrong, its easy for the whole team to be distracted by it, leaving no one focusing on sailing the boat. I had jumped on the helm when the problem unfolded and a quick glance down showed our speed at 4.4 knots. It was completely dark now and somewhere out there was Slyfox, sailing her angles and probably doing 10-11 knots. Suddenly our healthy lead did not seem that large. If we sailed another hour, going 4 knots slower than we had been, it was like giving 4nm back to all of the boats behind us. We had gone from thinking we had line honours in the bag and a shot at winning on handicap, to realising we might finish 2nd or even 3rd over the line now and well down the PHS standings.

Cook Island off Tweed Heads

Our finish line was an imaginary line from the sand-pumping jetty off Main Beach out as far as 800 metres to the east in a straight line. With its 'runway lights' and our chart-plotter it was relatively easy to know when you sailed past the end of it, even in the dark. We had been on a course directly to the end of the jetty on a course of 160 degrees doing about 5 knots. I found that if we pointed higher to a point 800m off the end of the jetty, the extra distance offshore reduce our true wind angle to 140 degrees and increased our speed to 6 knots and then 6.5 knots. All we could do now was sail as fast as we could on main sail only, with our spinnaker wrapped around our forestay and flapping noisily in the 16-18 knot breeze as our eyes searched the darkness for Slyfox's navigation lights.

Rod and Sean

"There they are" one of the crew called out. "Where?" I asked. "About 7 o'clock" said someone else, followed by Peter who said "6:45" to be precise. If you imagine where out bow is pointing (our direction) is 12 o'clock, then using clock time, easily communicates the direction of another vessel. This is important when up close and needing to act to avoid a collision. If you know the general direction of a vessel, especially if hidden behind sails, it makes a big difference in finding them quickly when helming. 8 o'clock meant they we on our left hand side and slightly behind us.

Karl up mast untangling the spinnaker once we are back on our marina berth

Our hearts sank as we watched their silhouette eating up the distance between us as quickly as they appeared to be going twice as fast. All we could do was wish down the distance to the finish line and hope we could hold them out. We were were down to 500 metres to go and still they kept coming, then 200m, then 100m and no they were at 8 o'clock. I watch the chart plotter eagerly for the line up with the sand jetty and our bowman Rob stood on the bow ready to give the the call as the lights lined up. We were more than 2-4 lengths in front as we crossed the finish, in the dark and with the angles it was hard to judge, but we knew it was just enough as we clocked our finish time of 7:45:40pm, 20 seconds ahead of Slyfox in the final results and enough to take out a well earned line honours win, our first ever in an ocean passage race.

We nursed the yacht back to the marina with the spinnaker flapping crazily as we motored 30 minutes to the sanctuary of our berth so we could tidy up our problems. Karl boldly offered to be hoisted up the mast in the bosun's chair, so he could be lowered down the forestay to untangle the mess and save the spinnaker from complete destruction. 45 minutes later our genoa halyard had to be cut free, but the spinnaker was saved and we were able to get it successfully back down onto the foredeck and bag in its bag.

We ended up finishing 4th on PHS, 28 minutes behind 1st place on corrected time. It was the 'one that got away' but winning on elapsed time by 20 seconds after 12 hours 45 minutes of racing was a great result for our team. PHS Results. All's well that ends well.

Madison, Rob, Karl and Alex

Race crew: Madison Hows, Rod Routh, Rob Westmoreland, Rick Durhan, Karl Schroder, Peter Chapman, Alex Lomakin, Sean Hanrahan and David Hows

-

Offshore Sailing

- 1 Jan 2022 Some thoughts on offshore sailing

-

Ocean Racing

- 19 Mar 2016 The annual SYC race to Julian Rocks, Byron Bay March 2016

- 28 Feb 2016 Surf to City Race January 2016

- 27 Feb 2016 Share my Ocean Gem Adventures

-

Trans-Tasman Crossing

- 29 Feb 2016 The Nina goes missing

- 28 Feb 2016 Getting to the Trans-Tasman startline

- 28 Feb 2016 Planning a Trans-Tasman July 2013

- 28 Feb 2016 It’s hard finding the perfect boat

- 28 Feb 2016 Introduction – Sailing the Tasman Sea

-

New Zealand Cruising

- 28 Feb 2016 New Zealand Cruising

- Australian Cruising